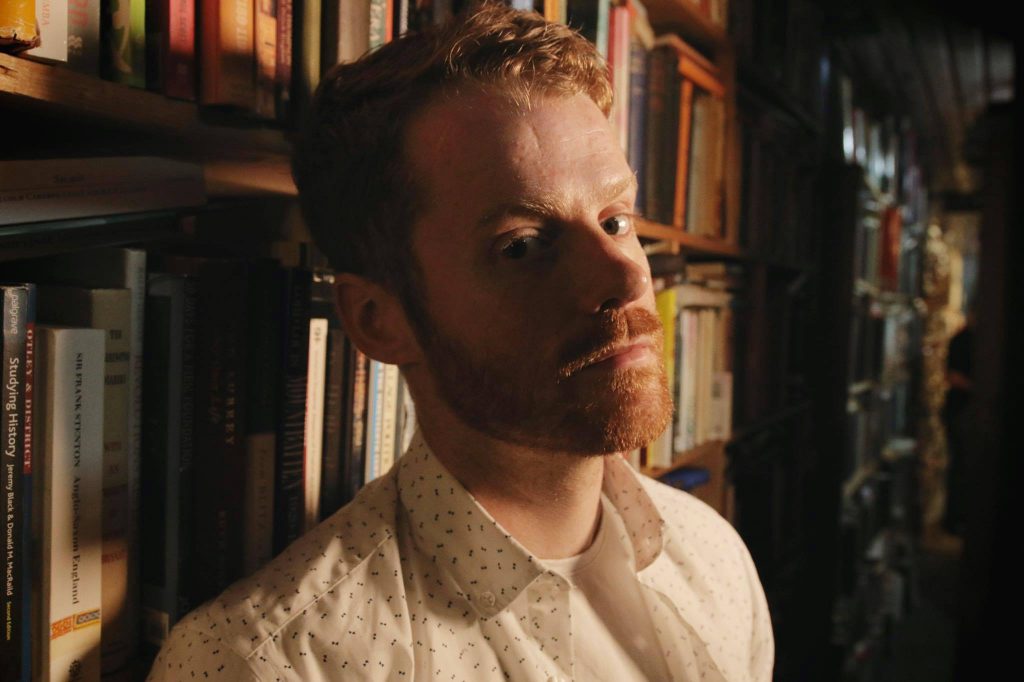

The 29th of May. 2 PM. Or is it AM? It’s hard to tell from the hiding hole he has constructed for himself in the spare room. Somewhere in Northern Ireland, in the quiet corner of his house, award-winning singer-songwriter Ciaran Lavery is hiding from the sunlight. “Like the vampire that I am.”

Or so he tells me over the phone. An international career and album campaign has come up against the same roadblocks that hit us all. Our meet up is the latest casualty. Lavery, however, is enjoying his alone time. He’s maintained a routine of sorts and has found himself chatting about his parent’s lives. “You’re accessing a whole different world there that I think is really interesting. Because it’s one of those things where you just don’t talk about it. I think that’s a generational thing. And then all of a sudden you’re at a wake and you start hearing stories. And you find out they’re much more of an interesting person than you initially thought.”

Stories and humans have always been paramount to Lavery. It’s what he’s built his career on. After all, it was releases like ‘Let Bad In‘ and ‘Shame‘ that put him on the map. Ever since, the blend of the public and personal has been a staple in all of his endeavours. Outside of music, however, he likes to keep to himself. “I find it endearing,” he says about the new romantic ideal of keeping secrets from social media. The lack of mystery brings with it a level of discomfort. “Maybe that’s just me,” but having some semblance of control has a certain attractive quality to it.

Indeed it’s control or lack thereof, that instructs the songwriters newest release. ‘Plz Stay, bb‘ (released June 26th 2020) documents a time in Lavery’s life that saw him grapple with himself. And he was determined to keep his fingerprints all over the project. First came the redacted press releases. Soon after, the bluesy ‘Can I Begin Again.’ Less a single, more a statement of intent. This time it’s different.

“This was the first time that I wanted to make it clear I am controlling all of this”. Writing started at a time when Lavery was looking to distance himself from his label when he was fresh off a particularly pressurised summer tour of The States. And so, ‘Plz Stay, bb’ had an air of intensity from the beginning. Sequestered in a studio with Danny Ball & Kris Platt, and alongside Matt Rutherford Jones & Dan Byrne-McCullough, Lavery kept the team & input concise to a small group of trusted people. This included contributions from friends & respected artists like Joe Furlong, Rosie Carney, Liza Anne, Deborah Sheedy, Dermot McConaghy & Thomas Camblin. “I was always trying to retain as much control as possible though equally relying on the team to have their own individual voices heard. I was, in the most obvious way, trying to show that this was not just an average album.”

Of course, the ‘sad singer-songwriter’ and the ‘This is my most honest work’ tropes hung over his head. So Lavery began to break down his creative process to its most basic and truthful form.”I had to make it quite clear at every step that I am handling this myself. Because how do you really know that (songwriters) are actually being as honest about it as possible? I wanted my own language to try and convince you that this is whatever it is. I was fully aware of the power I hold as the sole narrator. Is it the truth, or just my truth, or neither?”. Candour then became the central theme of the album, inviting the listener in for a gape, warts and all. “I have always tried to break the fourth wall. I was very conscious of showing people more, of lifting the curtain up and showing you how things really happen.”

The curtain does not just reveal the creative process, however.”I waltzed into the start of nine months of therapy at the tail end of that tour”. Initially armed with an ‘at least you’re not dead’ approach to his well being, Lavery surrendered himself to the idea that he was not fully in command. “I never really formulated the language to talk about myself. I didn’t ask myself too many questions.”

It took the therapy to inspire Lavery to write in a way that didn’t feel self-indulgent or deprecating. “I feel like that was my narrative for so long, and I felt like there’s more scope for honesty there.” He was encouraged to journal everything he felt, and before long he had started to capture a true snapshot of his life in his writing. “It wasn’t about me just airing all of my personal grievances against myself onto a page. It’s about the journey of therapy.” With such an emotionally weighted songwriting tool, he soon realised exactly what this album would become. Hence the opening verse of ‘Count To Ten‘. “There’s no boundary after that. I couldn’t be cryptic in my songwriting or skirt around things. It drew back the curtain, we were in this now.”

The discovery of a new language to express himself opened new doors. But while journaling became second nature, releasing the tracks was a different story. “I found it fun (to write the album). For the first time, I played around with sarcasm, comedy, melodrama. It only became difficult when I started to consider what would see the light of day”. Doubts and questions plagued campaign decisions. How best to promote this? Was this a fair representation? And how to avoid becoming the poster boy for mental health. “I’m not claiming to be an example to anyone.”

Following the writings of Irish poet Michael Hartnett and ‘Live or Die’ by Anne Sexton, he found a way to distance the man from the artist. And to combat the claustrophobia of pigeonholing. “Creatively, there’s no elbow room to do anything when you’re cast as the sad singer-songwriter. Because then you’re only this one-dimensional guy (laughs) it’s terrible! I’m not that person, its not what I wanted to do.” It was this desire to break the mould that led to such a difference for Lavery. “It’s one of the first times I’ve gone in with a solid idea. Which is the reverse of everything that I have ever gone in with before”.

He felt energised by this change and the musicians he found himself working with. Thus began an eagerness to flip expectations on their head. “I don’t want to have something that sounds really depressing, it needs to move. And I had a lot of these boys who didn’t come from a singer-songwriter world. They weren’t precious about this. Their parts became less than just accessories to what I was doing and very much worked almost in tandem.”

It started with the instrumentation, which was moved to the front. This allowed Lavery to properly experiment with the lyrics he wanted whilst maintain the driving spirit of the album. He revealed that he “played very little, I played more percussion than anything.” The players needed to shine. “I was trying to say something different. It was a way of clearing out the attic. And once you get to that point, there’s this sense of fearlessness that anything can go now”. The ability to grow and explore new sounds brought a new sense of confidence that informed the entire writing process. “I was surrounded by a different world and in this different environment, it was freeing, cathartic.”

We continued to talk about the album (“It was always rule-breaking”) and the idiosyncrasies that Lavery strove to include (on Funnier, “I wanted to sample this canned laughter, because for me it was unlike anything I had played with before”). And before long, we came upon the idea of rebelling against expectations, from his fans and from himself, of himself. Previously, the power of the song had originated “when the voice was about to break”. But as sessions progressed, he began to find new ways to capture that same crescendoing moment. “I loved that because it was accessing the same power from the fragility of a performance. Be that from samples, instrumentation or being incredibly mellow dramatic. Because I’d done that before. I wanted to try and get to that point without having to rely on this emotional, rehearsed performance.”

The brief anecdotes we shared about change resurfaced as Lavery began to comment on how this related to his creative work. “I wanted to see if I was a happy person. I wanted to know – was I going to have a career with music? Or was I always going to be the fella who had Shame?” A short pause before he continued. “I’ve stood in enough rooms and felt uncomfortable enough that made me feel like I was seven years old. I think that’s quite common for people when they are thrust into something that they are not familiar with. You become the tiny version of yourself. And I was haunted by the idea of ‘did I ever really make it’ and what is ‘making it’ anyway? I wanted to finally figure out how many sides of myself I can show you.”

At this point, all conversation about the album stopped and before long we parted electronic ways. Certain editions of Ciaran’s newest album come with a ‘Self Helplessness’ pamphlet. Its as melodramatic, desperately sad and funny as the album itself. The perfect companion and it reads like a conversation. If Lavery was searching for a new style, he’s certainly found it.

Comments 2